(When I launched the Advent Calendar of Science Stories series back in December, I had a few things in mind, but wasn’t sure I’d get through 24 days. In the end, I had more than enough material, and in fact didn’t end up using a few of my original ideas. So I’ll do a few additional posts, on an occasional basis, to use up a bit more of the leftover bits from Eureka: Discovering Your Inner Scientist…)

Every physicist with the tiniest bit of a public profile gets letters from people with a pet theory to promote. These days, email and social media make it incredibly easy to flood the inbox of any physicist known to the Internet with “exciting” “new” “theories” about… whatever. But this long predates modern telecommunications– I got my first kook letter by postal mail, in grad school, by virtue of being a co-author on a paper with “quantum” in the title.

So it’s always been a little amazing to me that two of the great discoveries of modern physics found their way into publication via the no doubt overloaded inboxes of famous physicists. The first of these was in 1924, in a field near and dear to my heart.

The story goes that Satyendra Nath Bose, a young theoretical physicist in Dhaka working as a Reader (the modern US equivalent might be an adjunct professor– he didn’t have a Ph.D., so he didn’t have full faculty status…) at the relatively new university there, was trying to teach Planck’s radiation law, but found the existing derivations unsatisfactory. After playing around for a bit, he found a new way of deriving the equation that didn’t involve bringing in some of the assumptions from classical physics that were used in the previous derivations by Planck and Einstein. He wrote up a short paper about this, and sent it off to a journal in London, which promptly rejected it.

He thought the idea had some merit, though, so he wrote up another copy and sent it off to the most famous physicist in the world, Albert Einstein, asking him to take a look, and if he found it interesting, to arrange for its publication in Zeitschrift für Physik. Wikimedia helpfully provides an image of his hand-written note, which includes the wonderful note “Though a complete stranger to you, I do not feel any hesitation in making such a request. Because we are all your pupils though profiting only by your teachings through your writings.”

(Bose did have a weak connection to Einstein, having been one of the translators of an Indian edition of Einstein’s relativity papers in English. He mentions this at the tail end of his letter, and this probably helped lift him off Einstein’s no doubt massive slush pile.)

Somewhat incredibly, Einstein read the paper, found merit in it, and translated it into German himself. He sent it to Zeitschrift für Physik along with a short follow-up of his own, and the two papers were published in 1924. This is the origin of what we now know as Bose-Einstein statistics, one of the essential underpinnings of quantum physics.

This was, as you might imagine, a career-making moment for Bose. He used Einstein’s response to leverage a trip to Europe, and spent a couple of years studying with various quantum luminaries, then returned to India. While he never did officially get a doctorate, he was given faculty status on Einstein’s recommendation, and had a long and successful career as a faculty member and administrator at several universities. Pretty good results from a fan letter.

The other great letter-to-a-famous-guy story comes a quarter-century later, and is more politically charged. After Lamb and Retherford discovered an anomalous shift in the energy levels of hydrogen, their discovery got a lot of media play. This included an article in Newsweek, which made its way across the Pacific to Japan, where it was noticed by Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and his research group.

Despite the utter devastation of post-war Tokyo, Tomonaga and his colleagues had remained active in researching theoretical physics, and had developed a new set of calculating techniques for tackling difficult problems in quantum physics. On hearing of the Lamb shift from the news article, they quickly threw their new methods at the problem, and successfully calculated the shift.

Tomonaga quickly wrote up a description of their work and results, and sent it off to another famous physicist, Robert Oppenheimer at Berkeley (these two probably had some more direct personal acquaintance, having both studied in Europe before the war, but I’m not sure). Oppenheimer received Tomonaga’s package of papers (which David Kaiser says was one of the first sent out of Japan as the American occupation gradually loosened restrictions on Japan’s contacts with the outside world) just after returning from the Pocono Mountain conference where Julian Schwinger (noted night owl) had just wowed the assembled physics luminaries with his own derivation of the Lamb shift using methods very similar to Tomonaga’s.

Oppenheimer recognized what Tomonaga had accomplished, and made sure it was reported in the Physical Review. There’s a nice bit of… irony probably isn’t quite the right word, but it’s hard to think of a better one, in the fact that Oppenheimer, who headed the Manhattan Project that made the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, was the guy to secure Tomonaga’s status as one of the co-discoverers of QED. I don’t doubt that Oppenheimer was aware of this, though I’ve never seen much discussion of his thinking on the matter.

So, while to some degree I hesitate to encourage the practice of mailing novel theories to famous physicists, it’s hard to deny that it has occasionally worked. So, I guess it’s okay. Provided, that is, that your theory is as brilliant and successful as Bose-Einstein statistics or QED…

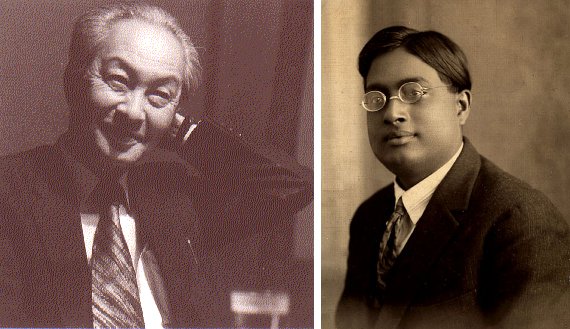

(The “featured image” at the top of this combines Wikimedia’s picture of Bose with The U. of Chicago Press’s picture of Tomonaga.)

So it can work… provided that you are already a practicing physicist, albeit less esteemed.

It has been pointed out to me (he says passively) that I had a detail wrong: Oppenheimer had already moved to Princeton by the time Tomonaga sent him his results on QED. My bad.

As for the “already a physicist” things, yeah, it helps to have something to establish credibility. Whenever I’ve needed to contact somebody about something for the book, I always lead with “I am a physicist and a professor at Union…,” which helps get me out of the probable-kook filter.

After receiving Bose’s letter and developing Bose-Einstein statistics, Einstein also predicted the existence of Bose-Einstein condensates at low temperature. This was independent of Bose’s contribution, and amazingly was done before quantum mechanics was fully understood. It also anticipated the experimental discovery by about 70 years. Just another example of how broad and deep Einstein’s contributions were, even if one ignores relativity.