(When I launched the Advent Calendar of Science Stories series back in December, I had a few things in mind, but wasn’t sure I’d get through 24 days. In the end, I had more than enough material, and in fact didn’t end up using a few of my original ideas. So I’ll do a few additional posts, on an occasional basis, to use up a bit more of the leftover bits from Eureka: Discovering Your Inner Scientist…)

One of my very favorite stories about a famous physicist concerns a young man of about 19, arriving at Cambridge from the University of Edinburgh. While being introduced around the college, it was explained to him that there would be a mandatory chapel service at 6am. “Mandatory?” he asked, and was assured that his attendance at the morning chapel was absolutely required. After some thought, he replied “Aye, I suppose I can stay up that late.”

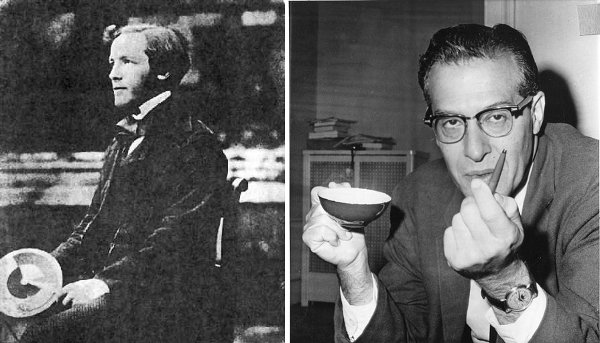

The young Scot in question was James Clerk Maxwell (pictured above as a young man; in later photos he sports a magnificently unruly beard), who made significant contributions to mathematics, the study of color, and thermodynamics, but is best known for showing that electricity and magnetism are, in fact, different aspects of the same thing. This basically completed a process begun by Faraday, who didn’t have the mathematical chops to put his notion of electric and magnetic fields on a solid theoretical footing. Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism are arguably the crowning achievement of nineteenth-century physics, and also set the stage for the twentieth century, because relativity grew out of attempts to reconcile them with Galileian ideas about relative motion.

Maxwell isn’t the only famous night owl in physics, though. He’s not even the only one to transform our understanding of electromagnetism. A bit less than a hundred years after Maxwell there was Julian Schwinger, who shared the Nobel Prize with Richard Feynman and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga for the development of quantum electrodynamics (QED), arguably the most precisely tested theory in the history of humanity.

Like Maxwell, Schwinger was a mathematical prodigy– after meeting the 17-year-old Schwinger when he was studying with Rabi at Columbia, Hans Bethe wrote to someone else that “Schwinger already understands 90% of physics; the remaining 10% should only take a few days.” Schwinger was sufficiently brilliant that people were willing to tolerate his odd work habits– specifically, his intense dislike of mornings. While teaching at Purdue in the 1930’s, he only grudgingly agreed to teach during daylight hours, and gave strict instructions to the department secretary to call him at home at noon to make sure he woke up in time for his afternoon class.

During WWII, he was given free reign to work as he liked best, and that leads to the best stories. For a short while, he was working on the Manhattan Project in Chicago, as part of a large theoretical team studying reactor designs. To accommodate Schwinger, a colleague who had worked with him before, Bruce Feld, served as a one-man “swing shift.” Feld would come in at noon, and spend the afternoon working with the theory team. When everyone else went home for the night, Feld would meet Schwinger, who was just waking up. Over Feld’s dinner and Schwinger’s breakfast– inevitably specified as “steak, french fries, and chocolate ice cream,” in biographical sketches of Schwinger– they would discuss what the team had done that day, then work into the night. Feld would go home at midnight, and Schwinger would continue until the wee hours, leaving notes for his colleagues to pick up in the morning.

This became even more extreme after he left the Manhattan Project, and switched to working on radar systems instead. While at the Radiation Laboratory at MIT, Schwinger worked a solo night shift, almost never meeting his colleagues in person. They would leave notes on his desk when they left at the end of the day, and return in the morning to find lengthy typed responses to all their questions.

The Schwinger story is, in fact, in Eureka already, which might seem like an odd choice for a book attempting to de-mystify science and scientific thinking. I prefer to think of these less as stories about what odd ducks Maxwell and Schwinger were, though, than stories about the flexibility and adaptability of science. The goal of science is to get results, in the form of theories and experiments that consistently described the universe in which we live, and in pursuit of that goal, you do whatever you need to in order to do your best work. If that means waking at 5pm and having ice cream for breakfast, well, that’s fine. Provided you’re getting good stuff done, scientists will adjust.

(My own thesis research, nowhere near on the level of Maxwell or Schwinger, was mostly done during late-night hours. I used to come in a bit before lunch, and fire up the lasers. While they were warming up, I’d analyze the data from the previous night and talk to other folks in the lab. About the time people on a normal schedule left, I’d start serious data collection, and run through to dawn, when I’d go home to grab a few hours’ sleep…

(Ironically, now that I have kids, my day has pretty much flipped– I get up before the sun, so as to be able to get SteelyKid and The Pip ready for the bus, and I do my best work before 9am. Mostly in coffee shops. I’m pretty much useless after 5pm these days.)

(The “featured image” above combines this Maxwell photo and this Schwinger photo from Wikimedia.)

1 comment

Comments are closed.