Copies of Eureka: Discovering Your Inner Scientist have been turning up in the wild for a while now, but the officially official release date is today (available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, IndieBound, Powell’s, and anywhere else books are sold). To mark that, here’s some stuff I wrote about the core message of the book, presented in Internet-friendly listicle form:

Eight Things You Need to Know About Science

1) Everybody Is a Scientist: Most people picture scientists as remote eggheads, who think in ways that ordinary people can’t comprehend, but the reality is very different. Scientists are not that smart, and ordinary people use scientific thinking all the time—in fact, every time you play cards, or sports, or even a video game like Angry Birds, you’re thinking like a scientist.

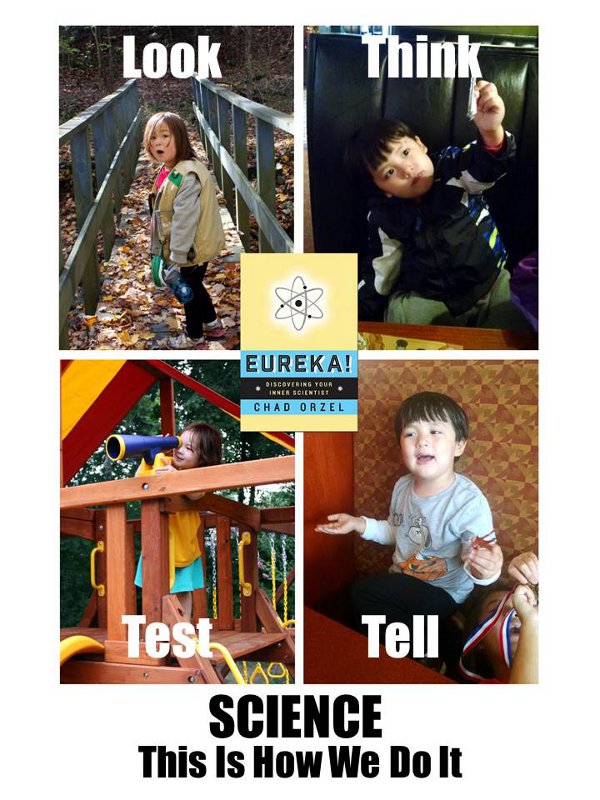

2) Science Is a Process: The basis of all of science is a simple four-step process: you Look at the world around you, you Think about why it might work that way, you Test your theory with experiments and observations, and you Tell everyone you know the results of the test. This is exactly the process you use in videogames: you look at the arrangement of pigs and blocks, you think about which block you should hit with which bird, you test your theory by launching birds, and if it works, you brag to your friends about how you cleared the level. It’s a process that’s part of everything we do.

3) Stamp Collecting and Biology: The scientific process starts with collecting observations about the world, in exactly the same way that people collect stamps, or coins, or rocks. And this can be crucial to scientific discovery. Charles Darwin wasn’t the first person to come up with the idea of evolution—his own grandfather was promoting evolutionary ideas sixty years before On the Origin of Species—but Charles became an icon of science because his theory was backed by mountains of evidence, collected over years of careful observation, a piece at a time, like so many stamps.

4) Card Players and Astronomers: Astronomers tell us that we’re surrounded by vast amounts of “dark matter” that we can’t see, five times as much as the matter we do see. This sounds downright crazy, but astronomers like Vera Rubin detected it through the same reasoning process used by a good card player. They used tiny clues in the light that we do see, together with knowledge of the laws of physics, to prove the existence of dark matter in the same way that a good bridge player figures out who’s holding the ace of spades without ever seeing the other players’ cards.

5) Jocks Are Nerds: The stereotype of athletes is basically the polar opposite of scientists: physically gifted, but not too bright. This couldn’t be farther from the truth—in fact, there are few activities more ruthlessly scientific than competitive sports. Success on the playing field demands constant thinking: making a mental model of what the other players will do next, which is then immediately tested, and refined for the next play. A major sporting event is several hours of high-speed science on display, and the winner will be the team that did the best job of thinking like scientists. This process of repeated making, testing, and refining of models is at the heart of science, and the same rapidly repeated process powers the atomic clocks that make GPS navigation possible.

6) Science Is Social: Movies and comic books are full of lone geniuses, great scientists whose lack of people skills force them to work alone. In reality, though, science is an intensely cooperative and social activity. Great scientists are almost always great communicators, and some of the most successful theories in modern science succeed because they tap into our love of story. And scientific discoveries always come from teams of scientists working together, whether in lab groups about the size of a basketball team, or the thousand-member collaborations that discovered the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider. Collaboration and communication are essential to success in science.

7) Science Is What Makes Us Human: The institutions of modern science are a recent development, but the process of science is as old as humanity itself. As far back as we have evidence of humans, we see people doing science. Ancient monuments like Stonehenge and Newgrange show this process in action: Stone Age people looked at the world and notice the motion of the Sun across the seasons, they thought about how to use that pattern to predict the seasons, they tested their theory over years, and they told their descendants the results, passing them down through centuries. With this knowledge, they built monuments that still work perfectly to mark the solstices, five thousand years later.

8) Science Is For Everyone: All too often we’re told that science is an exclusive club—that only men, or Europeans, or rich people are capable of science. These are toxic misconceptions. Science is the heritage of every human, and great discoveries have come from people of every gender, culture, and background. The only thing you need to do science is curiosity and a willingness to employ the process: Look at the world around you, Think about why it works that way, Test your theory, and Tell everyone what you find. It’s a process that we use every day, in hobbies and games. If we recognize that, and make more conscious use of the process of science, we all have the ability to improve our knowledge of the universe, and use to make the world a better place.

————

(Like this? Want to read more? Eureka: Discovering Your Inner Scientist is available from Amazon, Barnes and Noble, IndieBound, Powell’s, and anywhere else books are sold…)