I started out blogging about books, way back in 2001, but somewhat ironically, I rarely post anything about books any more. My free time has been whittled down to the point where book blogging is time taken away from other stuff, and it’s never been that popular here. I post reviews of science books that publishers send me, but fiction has mostly fallen by the wayside. As has fiction reading, to a large extent.

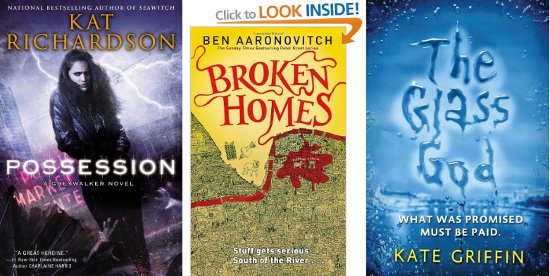

I did have a run recently of books with some elements that resonated with my own book-in-progress about scientific thinking, so I figure that’s a good excuse to bring them in. The books in question, pictured above, are Possession by Kat Richardson (the 8th of her “Greywalker” series), Broken Homes by Ben Aaronovitch (4th in the Rivers of London series, not out yet in the US), and The Glass God by Kate Griffin (2nd in the Magicals Anonymous spin-off from her Matthew Swift series).

“Wait a minute,” you might well be saying, “those are all ‘urban fantasy’ books with magic intruding on the real world. What’s that got to do with science?” The connection is that while they’re all books in which magic is real, they actually do a good deal to demonstrate the methods of science.

Richardson’s series follows Harper Blaine, a PI from Seattle who gets killed temporarily (seven books ago) by a small-time criminal she’s following, and when she’s revived finds that she can see and interact with all sorts of mystical stuff. There are glowing lines of magical energy flowing around, ghosts and snippets of old memories floating around, and the usual collection of vampires and other supernatural beings.

Aaronovitch’s series, on the other hand, features London policeman Peter Grant, who runs across a ghost at a murder scene, then finds himself drawn into the supernatural branch of the Metropolitan Police. A branch which has dwindled down to one superior officer, Thomas Nightingale, last of a supernatural corps that was all but wiped out in WWII. Peter finds himself tangled up with ancient gods and malevolent magicians in modern London, and has a wonderful narrative voice– snidely funny, and prevented from being grating smug by the fact that Peter’s a bit thick, and regularly gets tripped up by his own folly.

What’s great about these is that both lead characters find themselves dumped into a new magical world that they have to work out in detail. Harper is completely without a mentor figure– she meets up with an Irish witch whose husband is a scholar of mythology, and they provide some help, but they can’t provide any direct instruction, so she has to figure out what she can do and how to do it more or less on her own. Peter is technically apprenticed to Nightingale, but Nightingale more or less stopped paying attention to the modern world around WWII, so Peter spends a good deal of time trying to figure out the intersections between magic and modern technology.

In both cases, the magical systems have strict rules, and we get to see the characters figure them out by a more or less scientific process. Peter very explicitly does experiments on his new powers, working out how to keep his mobile phone from blowing up every time he casts a spell. Harper is less systematic about things, but again makes progress via trying things out, and building on what works. She also has a scientifically inclined partner who uses her reports about her experiences to devise some tools and techniques for interacting with the supernatural. It’s a nice demonstration of the basic method of science, in a context where you might not expect such a thing.

(Also, both series are blissfully free of Awesome Werewolf Boyfriends. Harper has some fairly realistic relationships with people who are decidedly mundane, and Peter is pretty hapless with women. There’s none of the chapter-length dithering about whether to get involved with the incredibly powerful and menacing but irresistably attractive supernatural being that ruins so many other urban fantasy stories. But that’s a personal taste thing, and has nothing to do with science.)

Griffin’s books, in both this and the parent series, come at the subject of magic from the other side. Magic in her universe isn’t rule-bound, but unruly– spells are accomplished using fascinating twists on the urban environment, or through cutting deals with vast and capricious supernatural powers. It’s a much better take on what magic would need to be like in order for it to actually exist and evade detection by science for the last several thousand years. If you were going to have real magic in the world, it would need to be something wilder and more organic than what you find in a lot of books, that practically come with their own D&D manuals– something that isn’t precisely repeatable and quantifiable. If it were, some smart young thing on the High Energy Magic faculty would’ve worked out how to do the Rite of AshkEnte with 4 cc of mouse blood by now. Griffin does a nice job of conveying that sense of magic as a wild thing.

So, all three of these are, in their way, a nice complement to my regular routine of thinking and writing about scientific thinking. They’re also all credible entries in their respective series. There’s a bit of an X-Files turn to Possession that may or may not work, but we’ll see in the next volume. Broken Homes involves a late plot twist that upset Kate, but has some awesome stuff along the way. And The Glass God did an impressive job of keeping me from having any idea where the plot was headed in a way that didn’t feel cheap; while considerably lighter in tone than the Matthew Swift books for the most part, it does have a dark moment near the end that again felt justified, not cheap. There’s a bit of a deus ex machina at the end, but since much of the book has been spent in search of the relevant machina, it’s not really a problem, and the arrival of the deus is pretty cool.

(Paul Cornell’s London Falling is working in a somewhat similar vein, and also quite good, but it turns on a plot point that will be rather upsetting for any parent of small children, so be warned if that describes you.)

(All three of these (four, if you include the Cornell) are very strongly located in particular cities where I don’t live. The Griffin, Cornell, and to a somewhat lesser extent the Aaronovitch all include large numbers of references to London geography that are undoubtedly highly meaningful to people who know the city. If, like me, you don’t know London, you’ll probably spend a lot of time feeling like you’re missing a joke; if that bothers you, be warned. Richardson is better about spelling out the Seattle-area history that she uses in her books.)

If those sound interesting, the first books in the respective series are: Greywalker, Stray Souls (which introduces the main characters for The Glass God) and A Madness of Angles (first in the parent series), and Midnight Riot (US)/Rivers of London (UK). They’re all really good reads up through the current books in the respective series.

I liked the London set books you mention (well, the first 3 Aaronovitch ones), and I just went to London this summer and really noticed the place references when I read The Glass God. (I dropped the Harper Blaine books after the second one, just kind of lost interest in them.) Good comparison to the Swift books — definitely darker and I think there’s more experiment/discovery in the “Magicals Anonymous” ones.

(Agreed on the Cornell book but I really liked that one, too.)

Sounds good to me. What’s important is _method_, teaching people how to think clearly, regardless of the subject matter. Any place that can get into fiction is good.

Chad, this is excellent: “Magic in her universe isn’t rule-bound, but unruly– spells are accomplished using fascinating twists on the urban environment, or through cutting deals with vast and capricious supernatural powers. It’s a much better take on what magic would need to be like in order for it to actually exist and evade detection by science for the last several thousand years.” That could be a premise for many new fiction plots, including in genres other than fantasy.

And, if per Arthur Clarke, magic is technology you don’t understand, then the reverse is also true: technology is magic you understand to the degree where it becomes mundane.

Or perhaps, technology appears as technology when it works with Newtonian regularity, and appears as “magic” when it seems more capricious and unreliable? That would explain a lot about the quasi-addictive psychology of certain elements of our modern world.