This post is part of a series of posts originally written for my blog at Forbes.com that I’m copying to my personal site, so I have a (more) stable (-ish) archive of them. This is just the text of the original post from February 2016, without the images that appeared with it (which were mostly fairly generic photos of college campuses).

The college admissions process goes year-round these days, but the activity and the associated stress level peaks twice a year: once in the fall, when high-school students have to decide what schools they want to apply to, and again in late winter/early spring when those same students are forced to make a decision about what college to attend. The process and the pressure on students has intensified considerably since my high-school days back in the 1980’s (after the dinosaurs but before the giant armored sloths), and as a faculty member, I’ve talked to dozens of students (and parents) over the years who are going through the process, many of them teetering on the edge of panic.

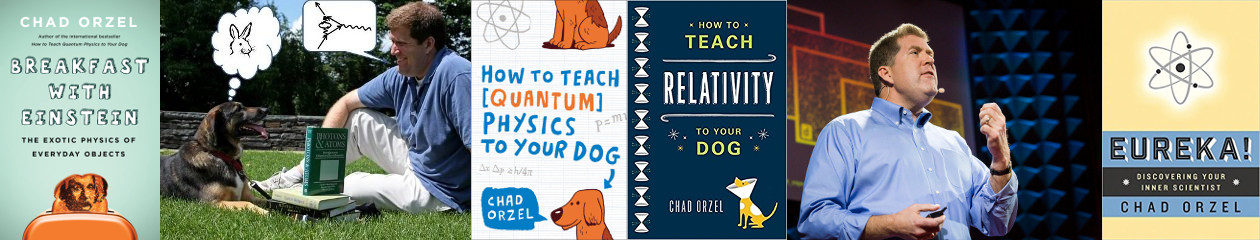

Having gone through this a lot– this is my fifteenth year as a professor– I have a well-worn set of advice I give to anxious high-school seniors on campus visits. Having previously offered a bunch of academic advice in blog form– why small colleges are great for students planning to study science, what students should do to prepare for studying science in college, why non-science students need to take science, and why science students need to take non-science classes— I might as well offer some general advice on the choice of college.

I will note up front that this is my personal take on the question of how to choose among multiple college admission offers, which I’ll assume are roughly comparable (that is, you’re not trying to pick between paying full tuition at one school and a free ride at another). While I’ll try to keep this as general as possible, I’m coming at it from the perspective of a scientist at a small liberal arts school, so if my answers seem to push toward small colleges, or seem more relevant for science students, well, that’s why. But here’s a version of what I’ve been telling students the last few years about choosing between different colleges.

1) Relax: The Stakes Are Lower Than You’ve Been Led To Believe

First and foremost, if you’re choosing between multiple reasonably good offers, you’re in a great spot, and will end up fine. In fact, if you find that you’re stressed out about the choice between multiple good schools, that’s probably an indication that it doesn’t much matter which of them you pick.

I say that because, ultimately, education isn’t something a college or university does to you, it’s something you do for yourself. Colleges and universities are in the business of providing resources for students to use in shaping their own education. Some of these are obvious– classes, labs, libraries– others more indirect– lectures, cultural events, fascinating fellow students– but in the end they’re all just tools that students will use to fashion their future selves.

And once you’re above a minimum threshold of viability, you can find the necessary resources to get a quality education just about anywhere. If you’re choosing between two roughly comparable institutions (that is, not comparing Stanford to the University of Phoenix) you will find all the tools you need to get a good education at either. What matters more than anything is that you’re actively engaged in the process, and trying to make the most of what your institution offers. The most important factor is that you care about your education, and if you’re worried about choosing between comparable colleges, that’s a good indicator that you have the necessary engagement.

(I should note that while this is largely a statement of opinion, I can cite some (social) science to back it up, in the form of two studies by economists Stacy Berg Dale and Alan B. Krueger. These show that while graduates of elite schools on average earn more than graduates of non-elite schools, students who could’ve gone to an elite school but didn’t for whatever reason end up earning just as much as those who went to the elite school. There’s a non-technical explanation here.)

So take a deep breath, and try to ratchet back the anxiety a little. The college decision is not an all-or-nothing, right-or-wrong choice– if you’re choosing between comparable institutions, you can be happy and successful at any of them.

2) Your Environment Matters

Given that education is mostly self-determined, the final choice among comparable colleges is to some degree an aesthetic one. That is, you want to choose the place where you will feel most comfortable, and most able to make use of the resources provided to you. And that means that things like the physical environment of the college are important to consider when making a decision. After all, you’re not just choosing where you’ll attend the occasional classes, you’re picking a place to live for the next several years.

I went to Williams College, back in the day, and a couple of my colleagues here at Union sent their daughter there a few years back. Sometime during her first year, one of them remarked to me that people who go to Williams seem to just love it to an extreme degree, and asked why that was. I said “Because the location scares off the people who would hate it.”

That’s only half a joke. Williams is in western Massachusetts, up in the Berkshires, and a long way from anything else. And lots of people from more (sub)urban environments find that really off-putting– my wife visited there as a high school student, and recalls thinking something along the lines of “This is nowhere.” To me, though, having grown up in a small town in a rural area of New York, it felt like home. That kind of comfort with the physical environment matters a lot. I know some classmates who really chafed at the confined atmosphere of living in Williamstown after a while, but for the most part, people who weren’t going to be happy out in the country didn’t go there in the first place.

So, if at all possible, make sure you visit the campuses of the places you’re choosing between (definitely do this if you didn’t get a chance before applying, but even if you’ve seen it before, go there again). If one of them stands out as feeling like home, that’s a good sign. More importantly, though, if you find you can’t imagine yourself living in a particular climate or set of first-year dorms, cross that school off your list immediately.

3) Your Classmates Matter

Even the most intensive academic calendar will see you spending well under a full 24-hour day a week interacting with faculty. Far more time is going to be spent outside the classroom, and unless you’re planning to be a total hermit, a lot of that time will be spent interacting with your fellow students.

So, as much as possible, try to get a sense of what the other students are like while you’re there. Sit in on a class or two, sure, and pay attention not just to what the professor says, but how the students act. And do what you can to get a sense of the social environment– don’t just go to classes, but try to find out what students are like when they’re not in class. If you’re on an overnight visit, hang out with your host and their friends, and go to any evening events the school has organized.

(This won’t be 100% accurate, of course, as a lot of colleges work very hard to keep prospective students far away from anything involving alcohol, but you can get some sense of what people are like as a general matter. The guys I stayed with when I visited Williams weren’t part of the same crowd I ran with as an actual student, but I had a good time just hanging around bullshitting.)

You’re potentially going to be spending a lot of time with these folks, and ideally some of them will become lifelong friends. Make sure there are people there you can feel comfortable spending time with.

4) Academic Environment Matters

It may seem weird to put this at the end of the list, but again, your education is going to be mostly determined by what you do. The faculty and staff are not without influence, though, so it’s very important to make sure that you’re comfortable with them, too.

So, if you know roughly what you want to study, make sure to visit that specific department, or a few departments in the right general area, and get a sense of that environment as well. Are the faculty willing to talk to you, as a prospective student, and make you feel welcome? More importantly, are they making the students who are already enrolled feel comfortable? It’s easy to put on a show for someone on a one-day visit, but harder to fake a comfortable environment for people who live there.

If you visit a department and see students hanging around working together, or working with faculty, that’s a great sign. If you go there on a weekday afternoon and the place is a ghost town, that suggests that students aren’t comfortable being there, which should make you concerned about whether you’re going to be comfortable being there.

And make sure the resources that a prospective college or university provides will be available to you. Having world-class research labs is a great thing, but if they’re entirely controlled by grad students and post-docs, they’ll make very little difference to your experience as an undergraduate. An awesome art collection or library that’s only open every other Tuesday from 8-9am isn’t going to do you any good.

(This is the point where my small-college bias shows through most clearly, of course– close contact with faculty and access to resources is what we’re selling…)

Again, I’m talking here about decisions between roughly comparable offers, so I haven’t said anything about finances or institutional reputation. The advice above presumes you’re deciding between schools whose prestige and price tag are similar, because that’s the situation for most of the students I see. Those factors aren’t completely meaningless– all else being equal, a more elite institution will offer you connections that you can’t get at a state school, and depending on what you plan to do after graduation, that network can make an enormous difference. And, of course, finances can loom very large– with elite schools having “sticker prices” north of $60,000/year, the size of a financial aid offer can be the decisive factor.

Those things are highly contingent on individual circumstances, though. The advice above is as general as I can make it, and applies to any college decision. Far and away the most important thing to remember is that education is something you do for yourself; after that, the decision is all about maximizing your chances of being comfortable with your physical environment, your classmates, and your academic department.