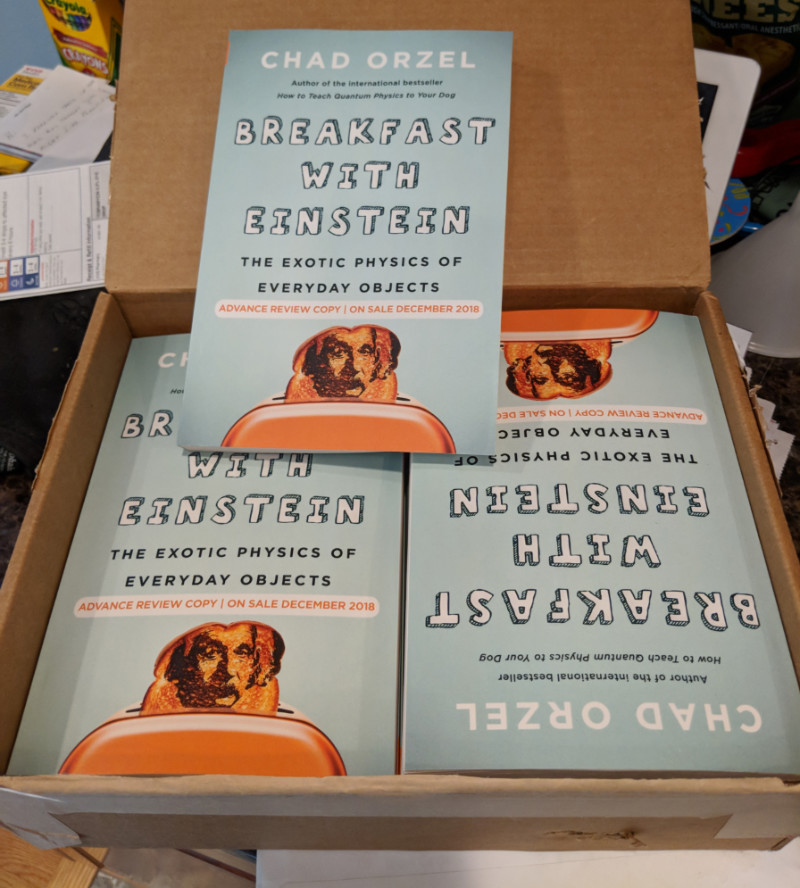

We’re entering the stage of Breakfast With Einstein publicity where I start doing interviews with radio shows and podcasts to promote the book. One of these sent me a list of questions which included “What’s your favorite motivational quote?”

That was surprisingly difficult, because I’m not much of an aphorism guy. I’ll probably go with Michael Faraday’s “Work. Finish. Publish.“, but really, when I want motivation, I tend to turn to music.

This got me thinking about the broader question of what I find motivational, though, which (as is often the case) led to me seeing related material all over the place. Around the same time I was looking at those questions, a bunch of people shared this survey from Nature about scientific career tracks. This is mostly self-reported information about salaries and job satisfaction, and thus a giant reminder of why I’m glad I don’t work in social sciences. Asking “Are you satisfied with your job and/or salary?” seems like the kind of thing that’s horribly confounded by individual personality: some people are going to be satisfied wherever they end up, others won’t be satisfied with anything. The hope is that these types sort of average out in the end, but I don’t know that I trust that.

The cross-sector (academia vs. industry) comparisons in that seem particularly problematic, given that those personality differences probably also drive some self-sorting into those tracks. That is, people who go into academia may do so because they prioritize different things than those who choose industry. I had a number of conversations with friends in industry jobs when I was coming up for tenure, and the mutual incomprehension was really notable: they looked at the concentrated stress of the tenure process and said “I don’t know how you put up with this bullshit,” whereas I find the idea of 30-odd years of background anxiety about job security equally repellent.

And, of course, that carries over into the financial domain: I’m happy to accept a lower salary than I probably could’ve gotten in industry in exchange for job security and working conditions I find much more congenial. It’s not that I don’t care about money, just that I care more about not having to put up with certain kinds of bullshit.

Of course, it’s not perfectly true that academics in general aren’t motivated by money. Academia is maybe a bit less true than in more nakedly capitalistic careers, but in my time as a professor I’ve seen a lot of surprisingly bitter fights over amounts of money that seem… not trivial, exactly, but certainly not worth the effort expended on them.

(This is probably a place to note that we are incredibly fortunate in financial terms: I’m paid well for what I do in my day job, the benefits package is very good, and I get some extra money beyond that from writing. That gives me the luxury of not needing to worry about having the money to do the things we want to do, and I’m absolutely aware that this is a luxury.)

Some of this is money as a proxy for status, of course, which is the other big common category of motivation that doesn’t excite me. I was a little surprised, after the announcement of this year’s Nobel Prize in physics, by how big a deal was made of new laureate Donna Strickland’s status as an associate professor. For those not in academia, that’s the second step in faculty rank: pre-tenure folks are Assistant Professors, tenured faculty are Associate Professors, faculty who have been tenured for a while can be promoted to simply Professor, and the truly distinguished get named chairs– the Donor McMoneybags Professor of SubjectArea. Strickland was still an Associate Professor, and this was considered outrageous by many on social media, to the point where arguments about that basically crowded out any discussion of the science for which she was honored, which is a shame.

It was especially a shame because the set of those outraged did not include Strickland herself. When asked about it in an interview, she said she felt sorry for the university, because it wasn’t their fault. She had simply never applied for the promotion, she said, because she didn’t feel like going through that process was a good use of her time. (She has since applied, and officially been promoted…)

(That interview also contains the charming story of her husband calling up a local food critic and asking “My wife just won the Nobel Prize, where should I take her out for dinner?” That’s one for the all-time list of cute laureate stories.)

The Strickland case loomed large in my mind because, like her, I’m an Associate Professor– technically the Gordon Gould Associate Professor at the moment, a named chair that’s rotating among several people because of some complicated history. I’ve been eligible for promotion to full professor for… four years? Five? something like that. I haven’t gone up for promotion for a bunch of reasons that basically boil down to “I don’t think it would be a good use of my time.” There’s a review process that involves a bunch of paperwork, and the aggravation of that (and the downside risk of being denied) is more demotivating than the title upgrade and salary bump are motivating.

Of course, while I’ve disclaimed interest in formal academic ranks as a source of motivation, that doesn’t mean I’m completely uninterested in recognition of one sort or another. I will freely admit that one of the reasons I’ve been blogging all this time is that I like having an audience. I try not to slavishly follow clicks, but I do tailor my Forbes blogging to some extent to emphasize things that draw more attention, and de-emphasize topics that don’t. (There’s money involved in that, too, but if I’m being honest it’s less about the money than the attention.) I enjoy doing media appearances of any sort, whether directly promoting a book or just answering science questions into a microphone and/or camera. I’ve come to love giving talks, and wish more people would invite me to do that.

As is often the case, the same factors that motivate me to Do Stuff can also become a source of frustration. I’ve been mildly annoyed on a continual basis since late 2014 that Eureka, which I think contains some of my best work, really didn’t find an audience (and especially at the way people keep having success pushing what I regard as much inferior theses about the same general area). It irks me at times that despite being in the business of talking science on the Internet for a loooong time (my original blog was started in 2002), I don’t often get recognized for that, and have seen multiple generations of hot new Internet sensations in science communication go by. There’s lots of stuff out there getting big play that I look at and say “I could do better than that. Hell, I have done better than that…”

A lot of that is self-inflicted, though. While I like speaking to an audience, I hate explicitly asking for one– it’s a good thing that I don’t need to make a living from writing alone, because I hate pitching things (and let’s not even talk about how bad I am at nagging people to pay me…). I’m not particularly good about doing the things that would make me more connected to the broader science communication community, which necessarily limits what I can reasonably expect in terms of recognition from that area. And I could certainly choose writing topics and modes that are more explicitly commercial (or at least commercializable) than what I generally do, but I’m easily bored and can’t really sustain that for a long time.

I’ve mostly made my peace with those self-inflicted limits, because on balance I’m happier doing the things that I’ve chosen to do than I would be pursuing a different course, but there’s still some nagging frustration there, and that’s part of what motivates me. “Those other people are doing it wrong” can be a very effective driver– God knows, it’s driven me to write a lot of blog posts at times when I really should’ve been doing something else.

Mostly, though, I do what I do because it’s fun. And, again, I’m incredibly fortunate to have the luxury of doing that. One of the things I buy by taking a lower salary in academia is the ability to work on whatever the hell I feel like working on (within reason), without anybody hounding me to produce results on a particular topic. And having a day job that pays the bills and provides health insurance means I can blog about whatever I feel like (and just as importantly not blog about things that bore me), even when it’s not a great source of clicks.

I have to admit that I’m a little surprised at how much this sort of stuff motivates me– I sometimes get snappish with the kids interrupting me when I’ve gotten involved in doing some project that isn’t remotely essential, but happens to be the thing that’s caught my interest for the moment. And I have at times taken on too many things on a “Sure, that might be fun” kind of basis in ways that aren’t particularly healthy: in the last month I made a day trip to NYC and two weekend trips to DC in close succession and as a result crashed pretty hard. I’m also lining up quite a bit of stuff around the new book and general physics stuff over the next several months, and am going to have to be careful not to overdo things.

On the whole, though, it’s worked out pretty well. Still not a great source of motivational aphorisms, though…